Please note: If you click through any links to Amazon below and make a purchase today, I may, as an Amazon Associate, earn a commission from qualifying purchases.

Have you ever wondered how your mind works? Why do you have vivid memories of childhood beach trips, but can’t remember where you put your keys? How can a five-year-old remember all the details about dinosaur species while you struggle to remember what you had for breakfast last week?

Exploring these questions and many more led Joshua Foer to write the entertaining Moonwalking with Einstein: The Art and Science of Remembering Everything.

From the opening narrative describing the one of the most famous memories in history, Foer draws you into an intriguing exploration of how our memory works, how it fails spectacularly, and how and why some people work to improve their memory.

The book starts with the story of how Foer first discovered the USA Memory Championship and how he was sent on assignment to write an article about it. Soon Foer finds himself challenging his memory with various techniques such as Memory Palaces and the Major System.

In each following chapter, Foer explores various aspects of memory.

One of the chapters explores what happens to people when their brain is injured or damaged. It describes a man who can’t remember anything recent, and yet somehow his feet know how to take him on his favorite walk.

Another chapter explores people who have exceptional memories. Questions asked include: do some people really have photographic memories? What is synesthesia and how can it help one have a better memory? It also describes a man whose memory was so powerful and overwhelming that he had to figure out how to forget things!

What I love about books like Moonwalking with Einstein is when a talented writer brings in topics that are unexpected to explain concepts. One memorable topic I learned about in this particular book is how to sex chickens (how to tell if they are male or female) and how an expert can sex a chicken in seconds when you or I would be hard-pressed to recognize the slight variation in their bodies.

Foer also capably explains how centuries of people used to remember things, including how much of history was passed down orally, and how that changed recently as the printing press and computers began to store our memories externally for us.

Interspersed with the interesting chapters on memory variants and the history of memory use in our current educational system are Foer’s descriptions of how he trained for the Memory Championships and his conversations with various memory experts.

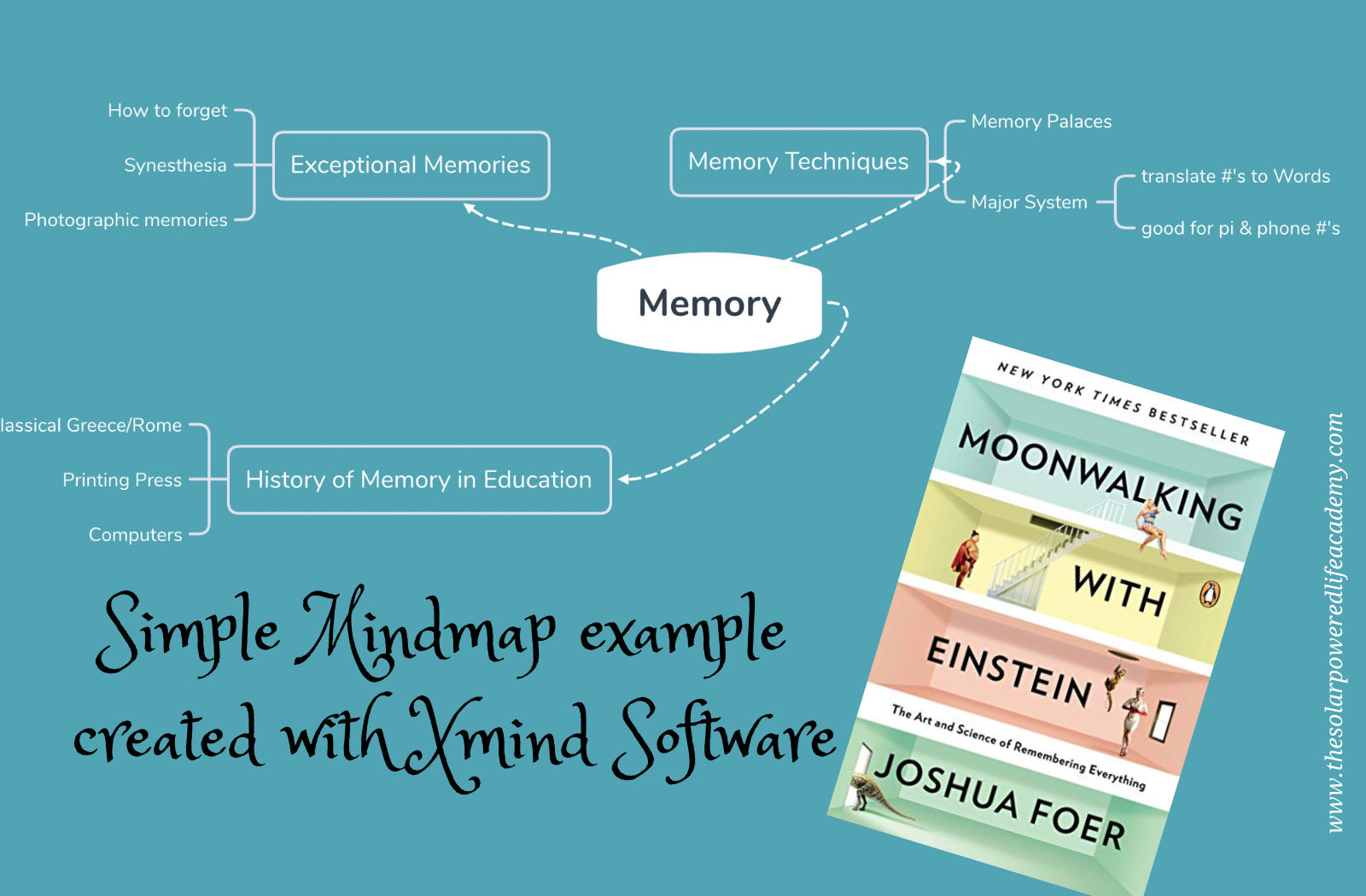

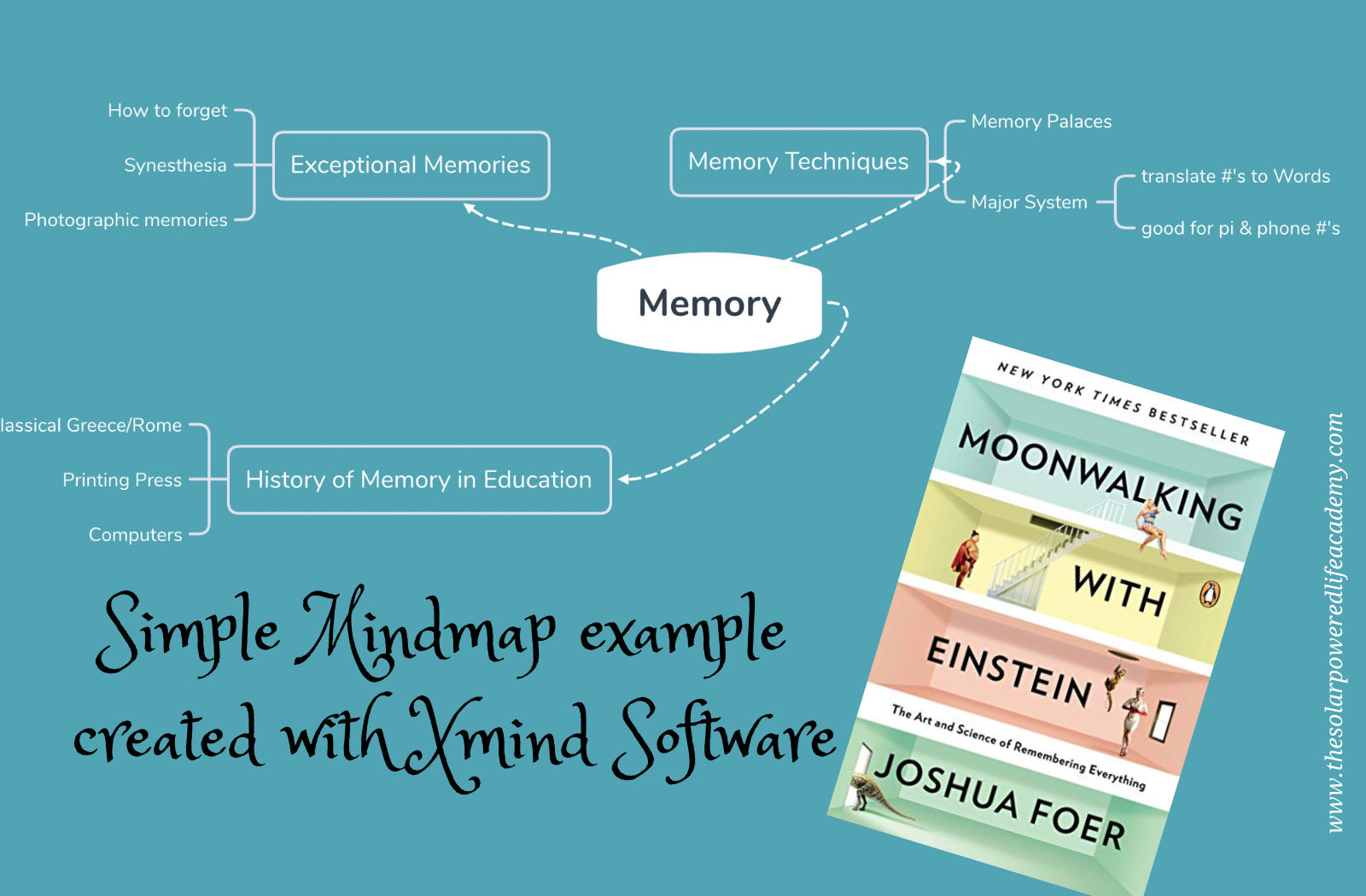

One expert consulted is Tony Buzan who is credited with naming and patenting Mind Mapping. Mind Mapping is a system of taking notes similar to brainstorming: instead of writing down notes in a linear/logical fashion, you write down keywords and images in an ever-expanding spiderweb of connections. (see example)

Proponents of Mind Mapping swear by it in part because it is another way to process the information in a memorable way. Instead of mindlessly reading the material and writing down a few concepts in the order they are encountered, mind mapping requires that you read the information, boil it down to the most basic points, and then visually connect those points to each other on paper through the map. It’s especially useful for brainstorming and organizing information.

Foer also spends a lot of time describing how he uses Memory Palaces.

Memory palaces are when you intentionally use a place you know well to place your memories. This works best when you make your memory more memorable through weird associations, colors, and other tricks. For instance, you might memorize a deck of cards in order by placing the Jack of Hearts at your front door, the 8 of clubs hanging on your coatrack, the 3 of diamonds as you enter your living room, and so on.

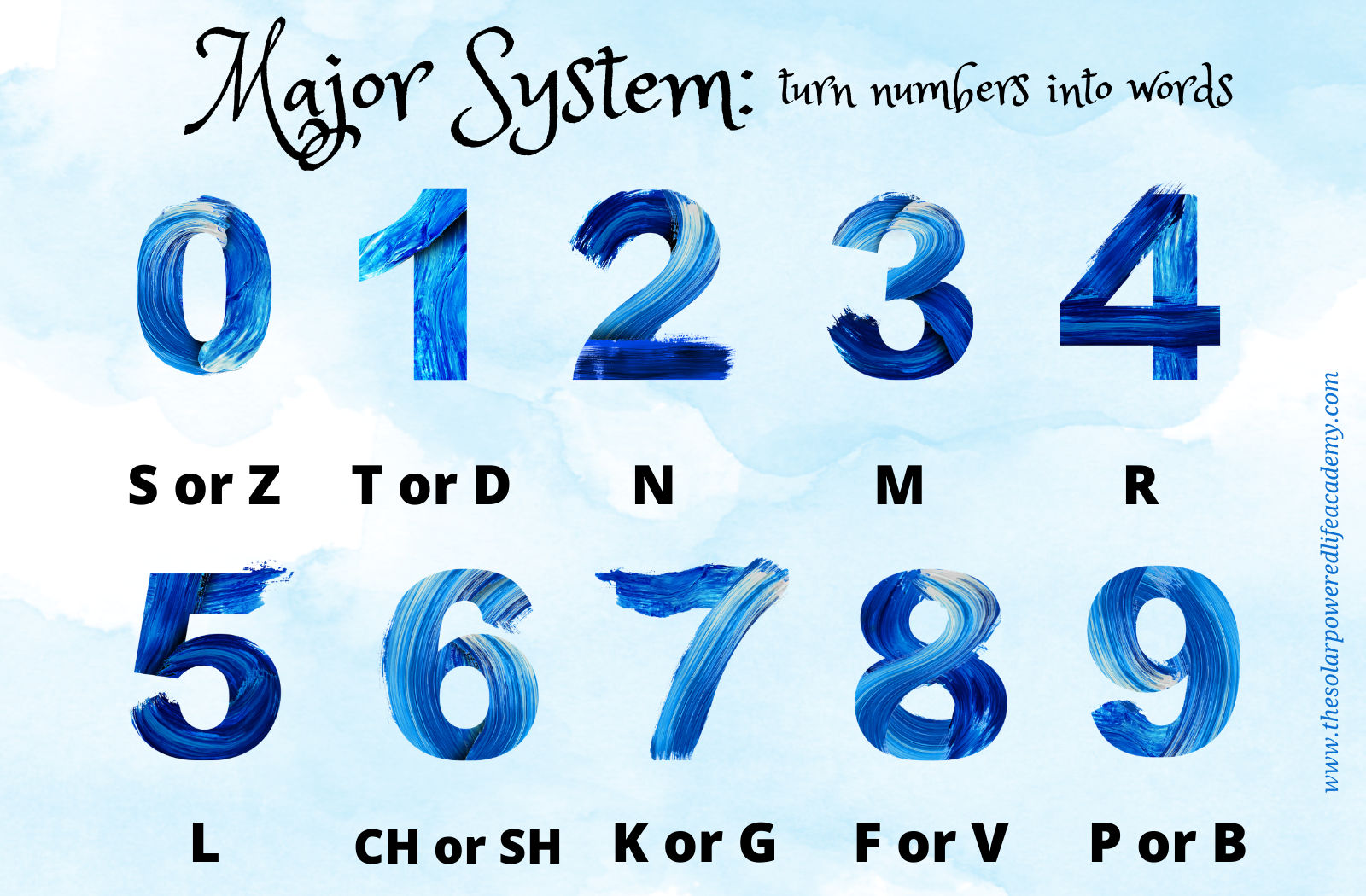

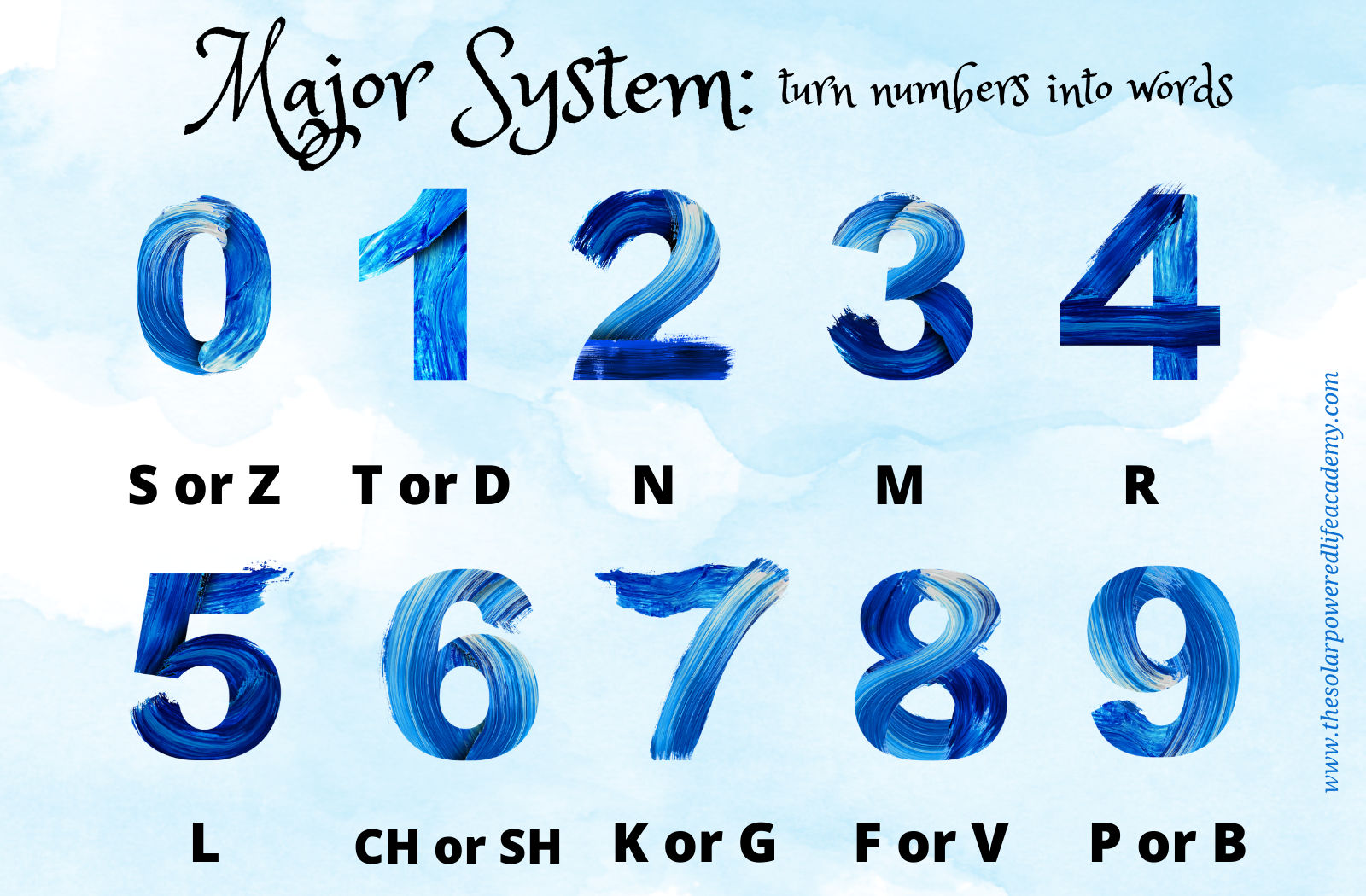

Foer also describes the Major System, also known as the phonetic number system: a system of memorization possibly first devised in the 17th century by Pierre Hérigone. It assigns various numbers to consonant sounds which then makes it easier to remember the numbers. For instance, the number 8274 could be translated to “finger”.

I actually learned the Major System a few years ago when I signed up for an online class with Jim Kwik (the author of the newly published book “Limitless”, which I am currently reading.) The numbers are assigned to consonants as follows:

So, to translate a number into a more memorable word, you just add whatever vowels you want to the consonant sounds so it becomes a word. For instance, 53150 would become L – M – T – L – S or Limitless.

To make memories stick, though, you need to make them memorable. Imagining famous celebrities doing awkward things is much more memorable than just rote-memorizing the Jack of Hearts, 8 of clubs, and 3 of diamonds.

Combining Memory Palaces and the Major System helped Foer memorize packs of cards and random lists of digits in order to prepare for the Memory Championships, but one could also use it to memorize important historical dates for a history exam or even to help you remember your credit card number or phone number.

One of my favorite chapters explored the “OK Plateau” or that place where you become just competent enough at something that you quit trying to improve. He rightly points out that many of us learn how to drive just well enough to keep our cars on the road and out of accidents, but how one must work much harder to learn how to drive as well as a race car driver.

Throughout the book, Foer examines our relationships with our memories and explores the concept of who is “smart” and how someone becomes truly intelligent. As he puts it:

When information goes “in one ear and out the other,” it’s often because it didn’t have anything to stick to….I spent my time in Shanghai roving around the city like any good tourist, visiting museums, trying to get a superficial grasp of Chinese history and culture. But my experience of the place was severely impoverished. There was so much I didn’t take in, so much I was unable to appreciate, because I didn’t have the basic facts to fasten other facts to. It wasn’t just that I didn’t know, it was that I didn’t have the ability to learn.

If all knowledge is compared to a spider web, then intelligent people have just had the opportunity to gather more knowledge and relate it to other knowledge. Foer points out that our current educational system does a poor job of making students memorize all of those facts and figures that past generations knew and therefore makes it harder for students to remember “all of that stuff”.

If you’re looking for a book that is an entertaining read while teaching you some handy memory and study tricks, try Moonwalking with Einstein.

Then let me know what you think!

Please note: If you click through any links to Amazon on this website and make a purchase today, I may, as an Amazon Associate, earn a commission from qualifying purchases.